A God Awful Painting

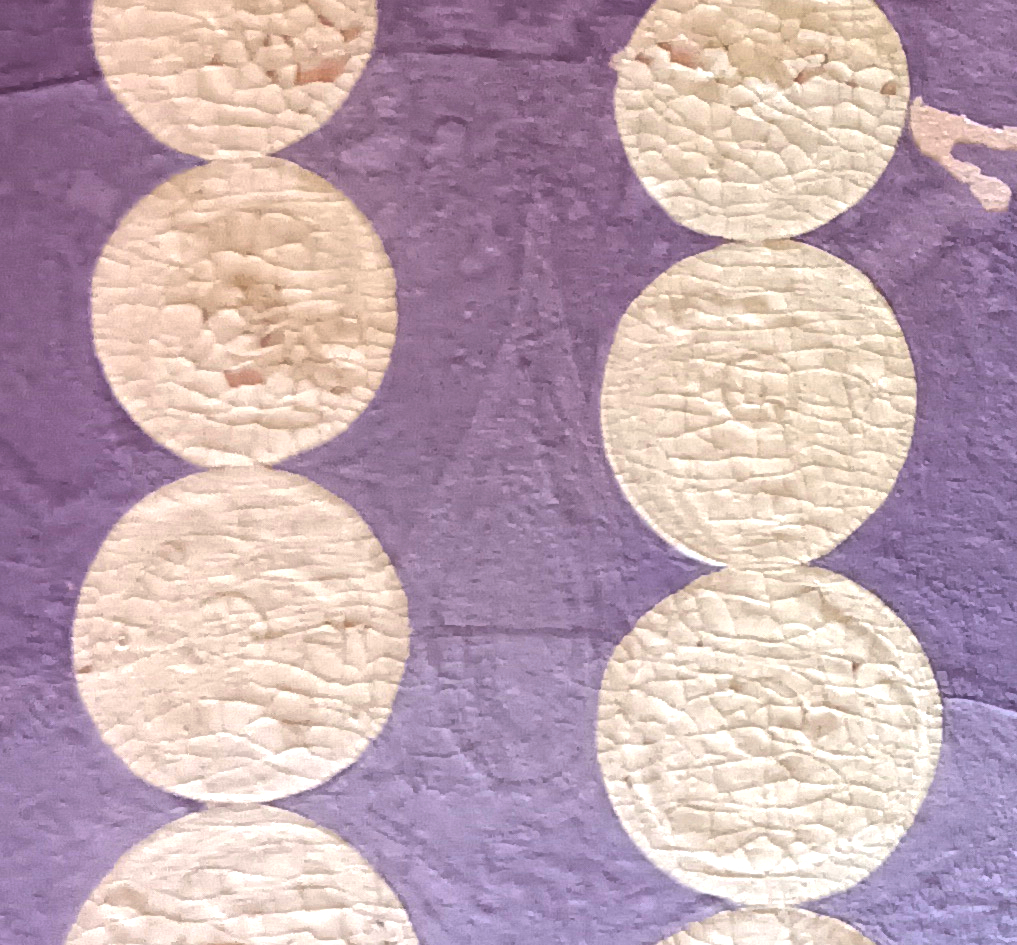

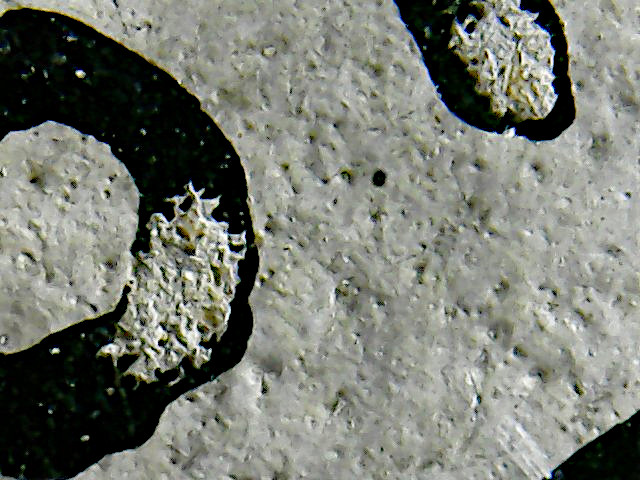

Above:

Almost invisible until the light caught it—a ghostly painted droplet. Proof, perhaps, that there was more here than meets the eye.

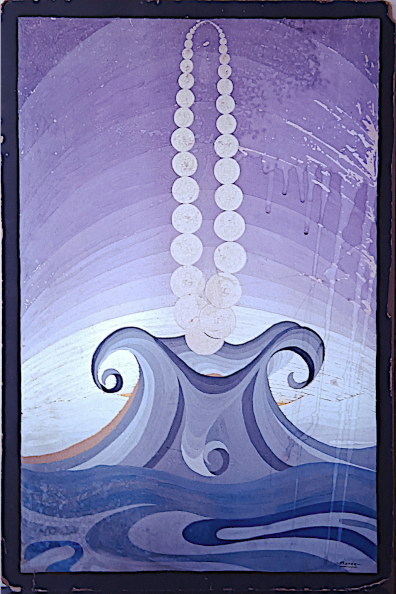

A Decorative Surface That Doesn’t Hold

At first glance, Morée looks like a celebration of early Art Deco. Ornamental curves.

Stylized symmetry. A vertical rhythm that draws the eye gracefully downward.

Even the pearls suggest elegance—refined, feminine, balanced.

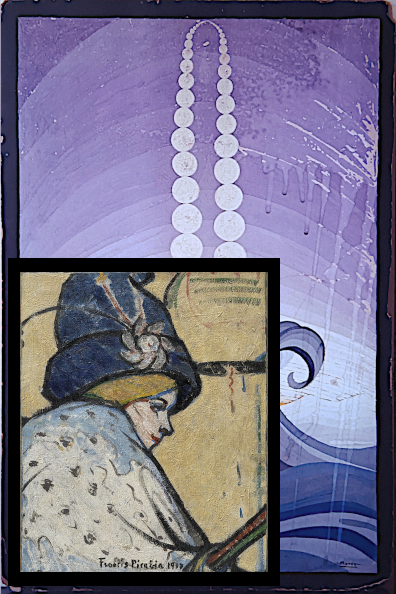

It could almost pass for a fashion illustration or the cover of a 1920s magazine—

poised, formal, deliberate.

It’s even signed Morée —a name that subtly echoes a famous illustrator, Erté.

This reading holds—until it doesn’t.

Because some things start to slip. The symmetry strains. The elegance wobbles.

And the pearls… they’re not doing what pearls usually do.

They’re the most telling clue. At first, they seem to rise—from the water, like

an offering, like something being born or created.

But look closer: at the top, the strand is facing the viewer head on, then slowly it twists to the left near the wave. Now they are not rising. They’re being lowered.

Why Would Someone Drown Pearls?

In 1916, pearls meant something. They weren’t just decoration—they were symbols:

of status, class, beauty, femininity, wealth.

For a certain kind of artist, those meanings had begun to curdle.

It wasn’t the painting that was left in the rain. It was the pearls.

Glamour isn’t just being mocked—it’s about to be drowned.

This painting isn’t anti-beauty. It’s anti-beauty-as-power.

A quiet execution of prestige.

The Signature Wasn’t Safe Either

First, we think we’re watching the ocean give birth to pearls—

but we end up watching them drown.

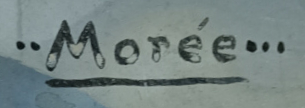

Then the name: even the signature has been attacked.

Scraped with a sharp object, partially removed, partially defaced.

Someone didn’t just want to sign this painting.

They wanted to unsign it.

The Name Was A Setup

The name Morée is already strange—ornamental, elusive, and almost completely unattested in the historical record. That in itself raises a flag.

But its elegance feels deliberate. The accented “é,” the soft flourish—it echoes another name known across the early 20th-century art world:

Erté, the pseudonym of Romain de Tirtoff, whose Art Deco illustrations were defined by high fashion, surface brilliance, and stylized femininity.

If Morée was chosen to mirror Erté, the signature wasn’t just a flourish—it was a mask.

A stylized name, crafted to evoke the very aesthetic the painting would sabotage.

But then it gets stranger. The signature isn’t just fake—it’s damaged. Scraped.

Partially removed with a sharp tool.

That act doesn’t just undo authorship—it turns the pseudonym into a target.

The name was borrowed to evoke glamour—then attacked to reject it.

It wasn’t signed. It was unsigned—twice.

But the unravelling was not over.