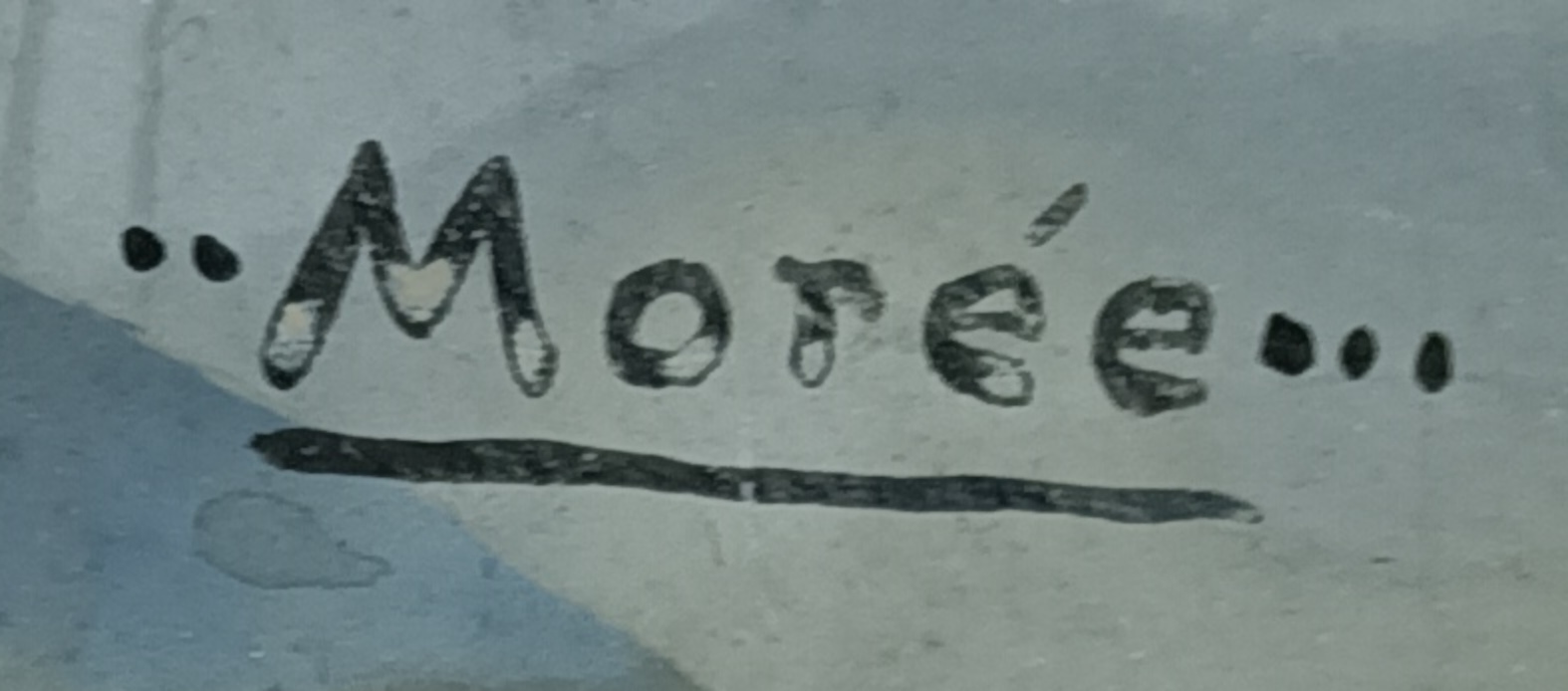

The Signature

.. Morée ... — The Signature

Long before anyone saw Morée, at least one Duchamp scholar—John F. Moffitt—was already speculating that the dotted motion-arcs in

Nude Descending a Staircase

might symbolize pearls, linking the figure to Belle Haleine and Rrose Sélavy’s costume. Even before Morée, the idea of pearls was already in the air.

Marcel Duchamp Leaves His Mark

One small but persistent mystery in Morée is the signature—two dots before “..Morée…” and three after. An odd bit of punctuation. But in Duchamp’s world, small details often signal something larger. We believe that the dots slotted Morée between Nude No. 2 and Nude No. 3 —not as a formal continuation, but as a sort of retroactive correction.

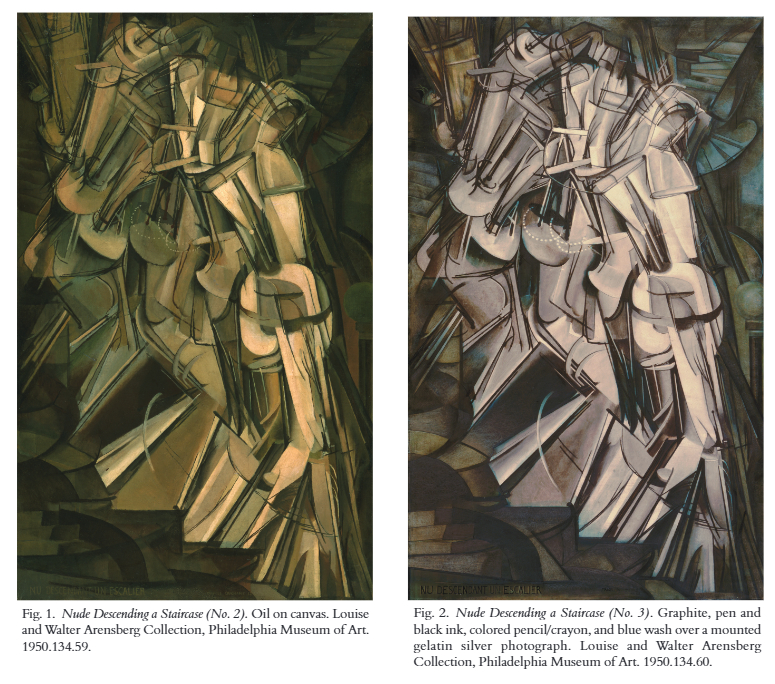

Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 and No. 3.

Many critics have described No. 2 as mechanical, faceless, and abstract. But in doing so, they may have overlooked one of the painting’s few humanizing gestures. The elliptical arcs at its center—what we now call the “pearl-like” forms—were often interpreted as motion diagrams or anatomical joints, but that was likely not their intended meaning. To Duchamp, they were ornamental: a subtle feminizing touch that went largely unnoticed.

And the familiar reading of “motion rings” may deserve a second look. Rings imply circular motion, but the figure in the painting does not turn. It descends, bends, and pivots. The arcs don’t trace a path—they mark adornment. Ornament.

Pearls. A humanizing gesture. A feminizing one. But most people missed it.

The Dual Function of Morée

Duchamp did not revise No. 2. He did not explain. Instead, he let Morée speak. What began as an independent act of sabotage became, after the fact, a form of historical repair.

The signature—two dots before, three after—was not an encoded name. It was a timeline. A repositioning. A quiet assertion that Morée belonged between the two Nudes, not as part of a sequence, but for clarification.

It didn’t echo No. 2 or anticipate No. 3.

It clarified what had always been there.

What most had failed to see.

Nude No. 3: Clarifying the Message

When Duchamp painted Nude No. 3 in October 1916—a near replica of No. 2—he seems to have had the revelation: Morée could bridge the gap. Quietly. Indirectly. That’s when the refinement begins.

In No. 3, the elliptical arcs are no longer ambiguous. Rendered with greater care, they read unmistakably as ornament—as pearls—not as motion lines. What had been missed in No. 2 becomes harder to ignore in No. 3.

And Morée becomes the key. The painting that says: “Here’s what you missed.”

The Dots Were Added Later

At some point, probably after Nude No. 3 was completed, Duchamp added two dots before the title, and three after:

..Morée…

This was not punctuation. It was citation.

The dots quietly slotted Morée between Nude No. 2 and Nude No. 3 —not as a formal continuation, but as a correction.

A way to reframe the nudes without repainting the past.

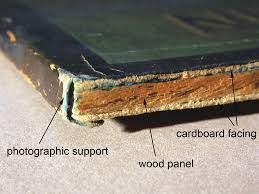

In order to assist in creating a high fidelity replica, Nude No. 3 was painted over a photographic enlargement and mounted on wood.

This photo enlargement has one very distinct feature: a black photographic border framing the entire image.

It’s likely not accidental. It echoes the black border in Morée.

An early citation.

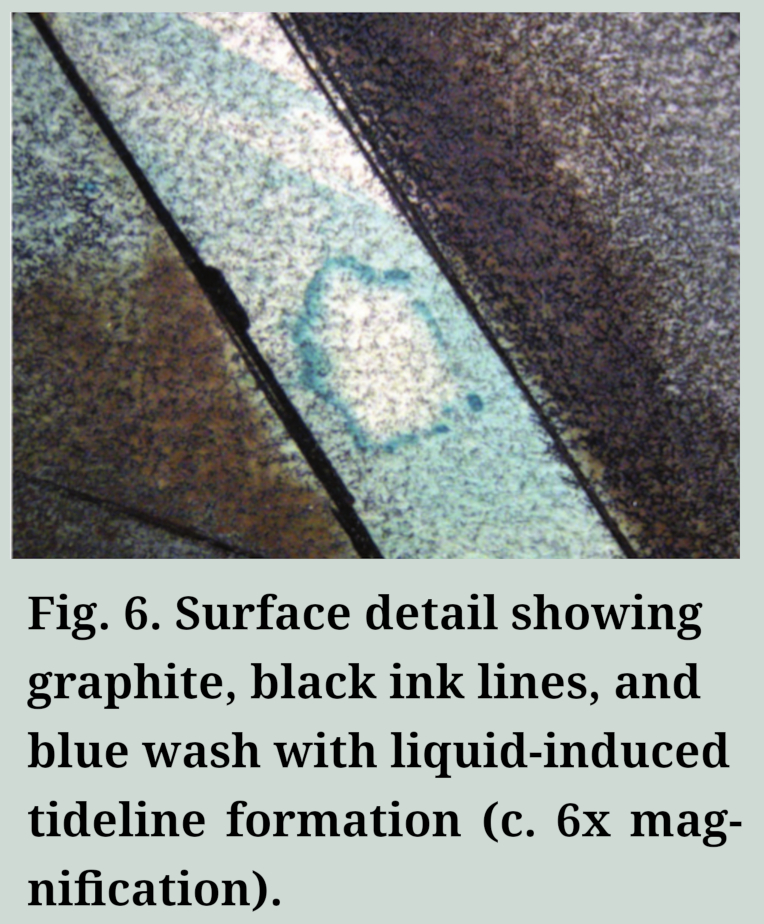

One more possible link: Conservators believe a drop of alcohol or solvent hit the blue ink wash in No. 3, causing the pigment to repel and create a distinct halo.

This could be just an accident, or it could be intentionally created. It is known that Duchamp used