Vandalism as Vision

The Stain Is The First Thing Most People Notice.

But It Should Be The Last Thing They Dismiss.

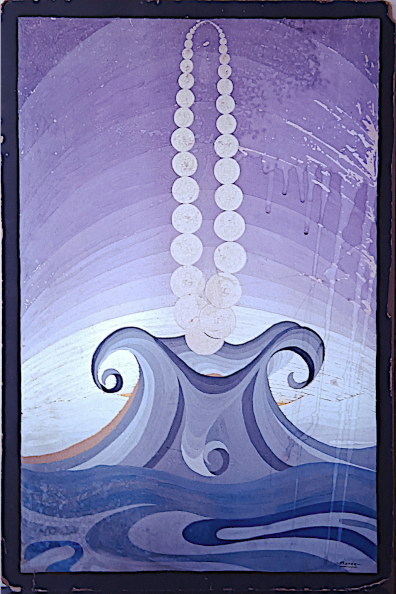

Yes, it looks like water damage—until you realize this isn’t an abandoned painting. It’s been carefully constructed, then deliberately dismantled.

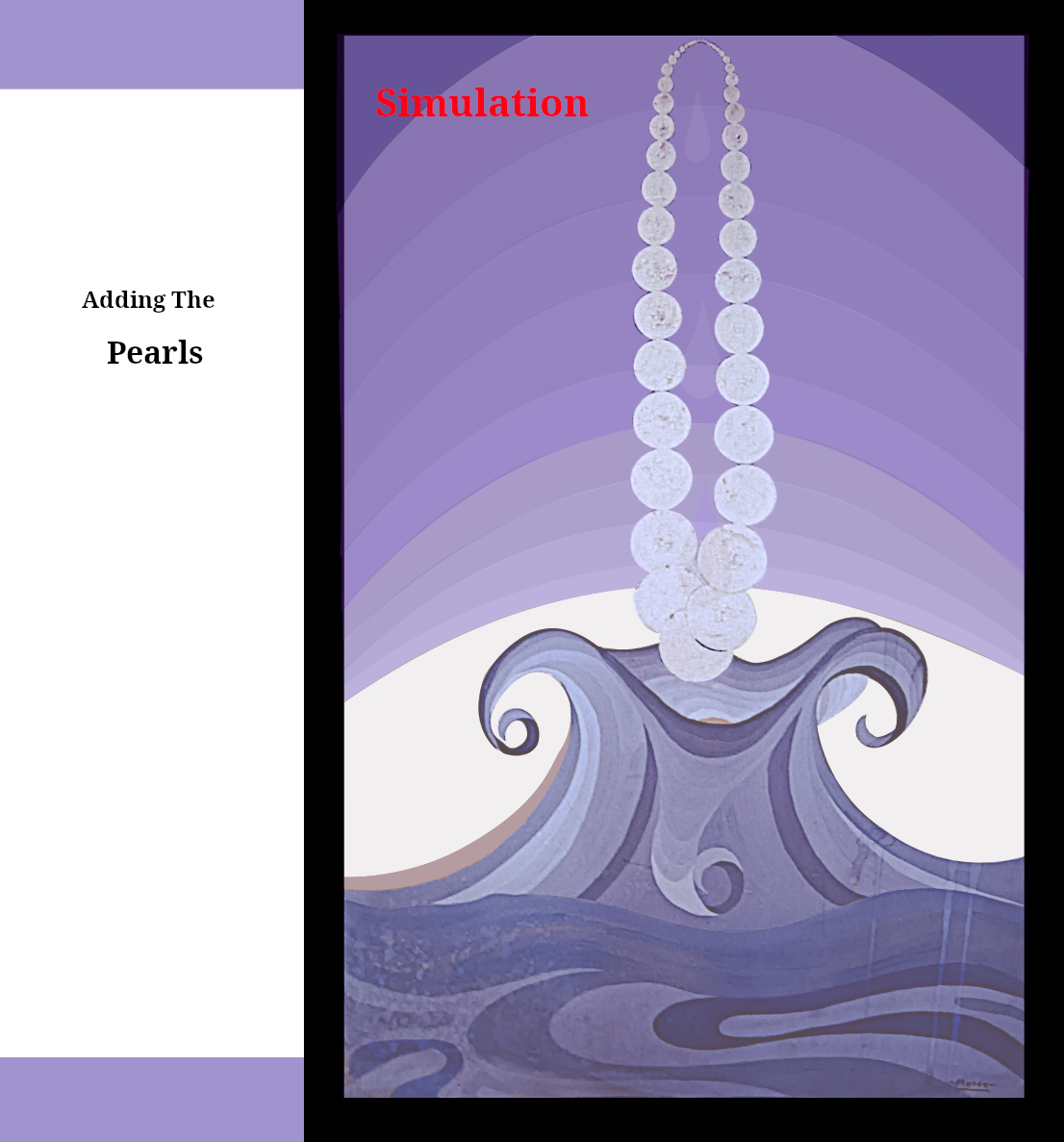

The pearls don’t rise; they’re being lowered. The name isn’t just strange—

it’s a pseudonym made to echo Erté. And then the signature gets scraped away, as if authorship itself were being revoked.

So with all that sabotage already in motion—

why wouldn’t someone stain the surface?

Why not go one step further?

Why not go all the way?

Why not disfigure the image entirely—if that was the point?

What looks like damage might be part of the vocabulary.

Not just defacement—but defiance.

Not vandalism in spite of the image—

but vandalism as the image.

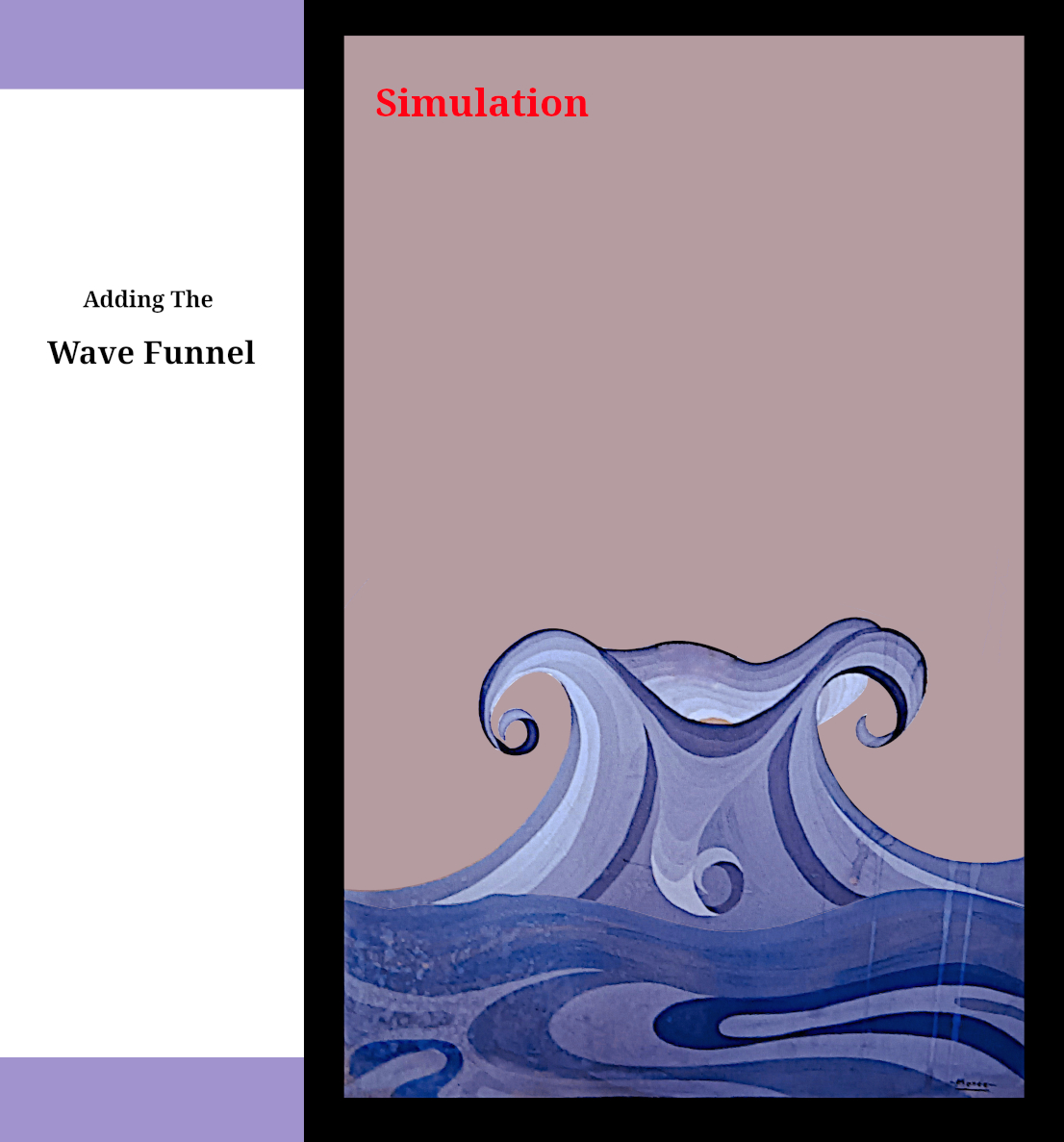

This Painting Was Built to Be Unbuilt

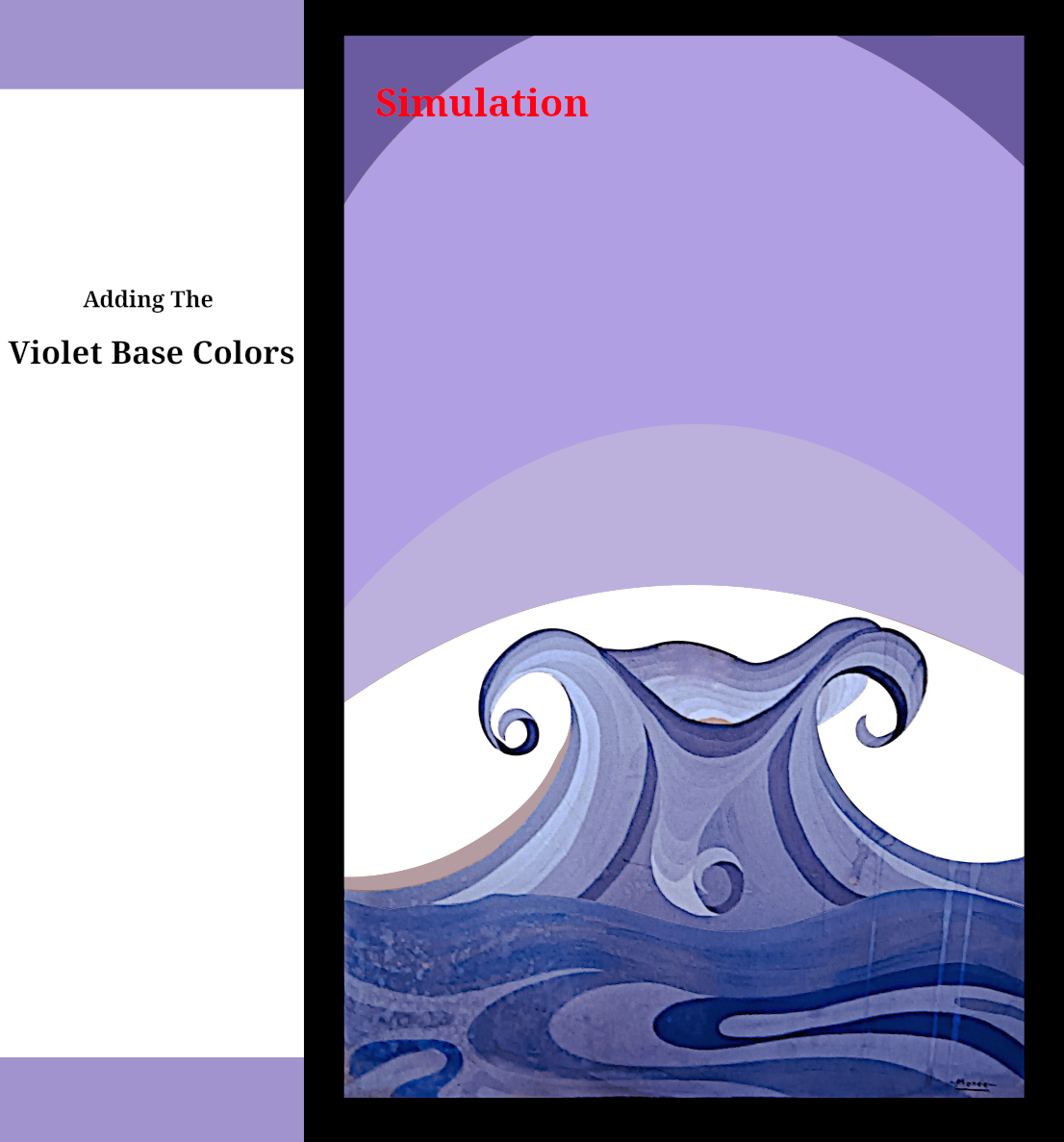

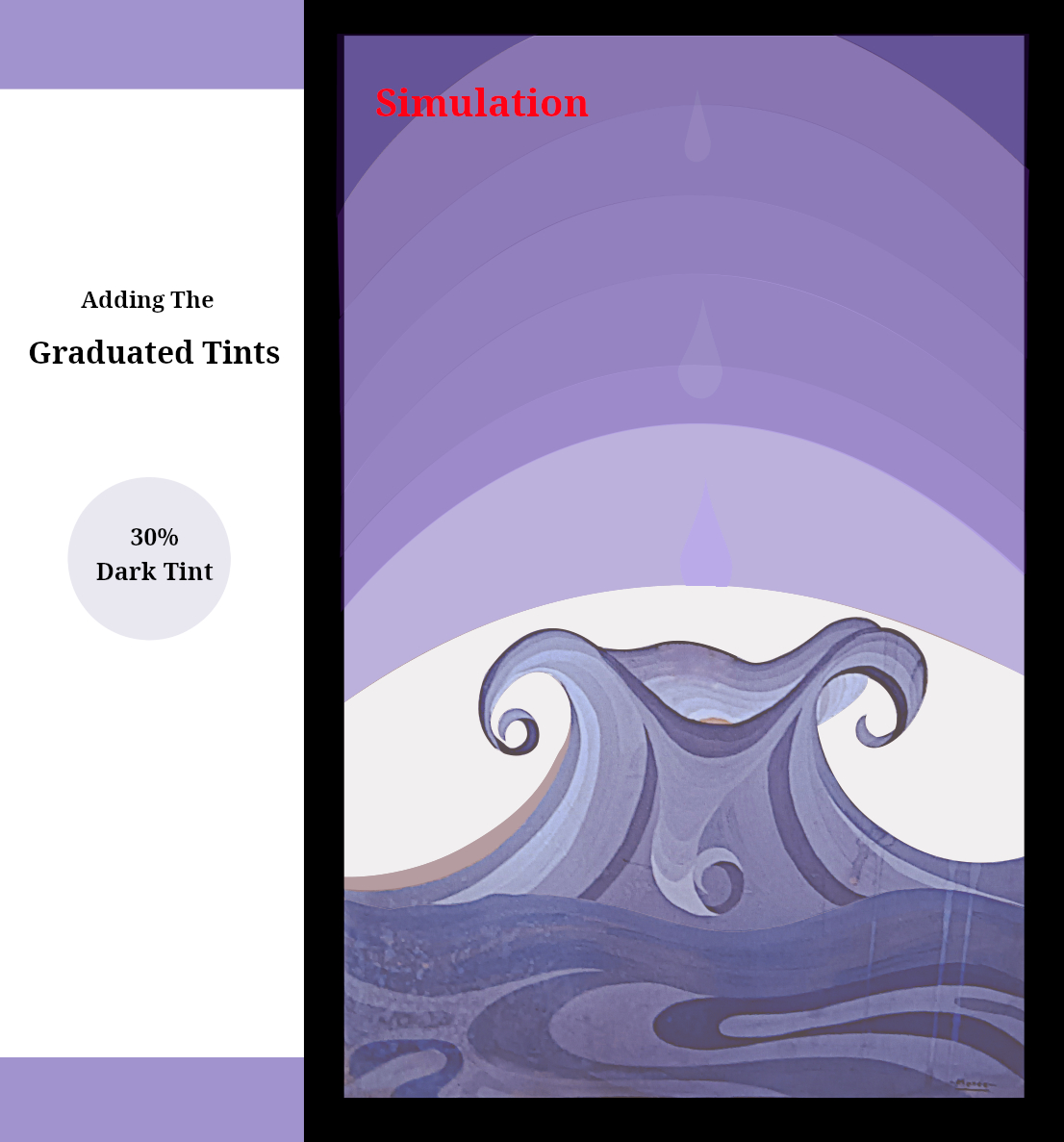

One of the clearest signs that the stain was deliberate isn’t the shape, the discoloration, or even the direction of the drips.

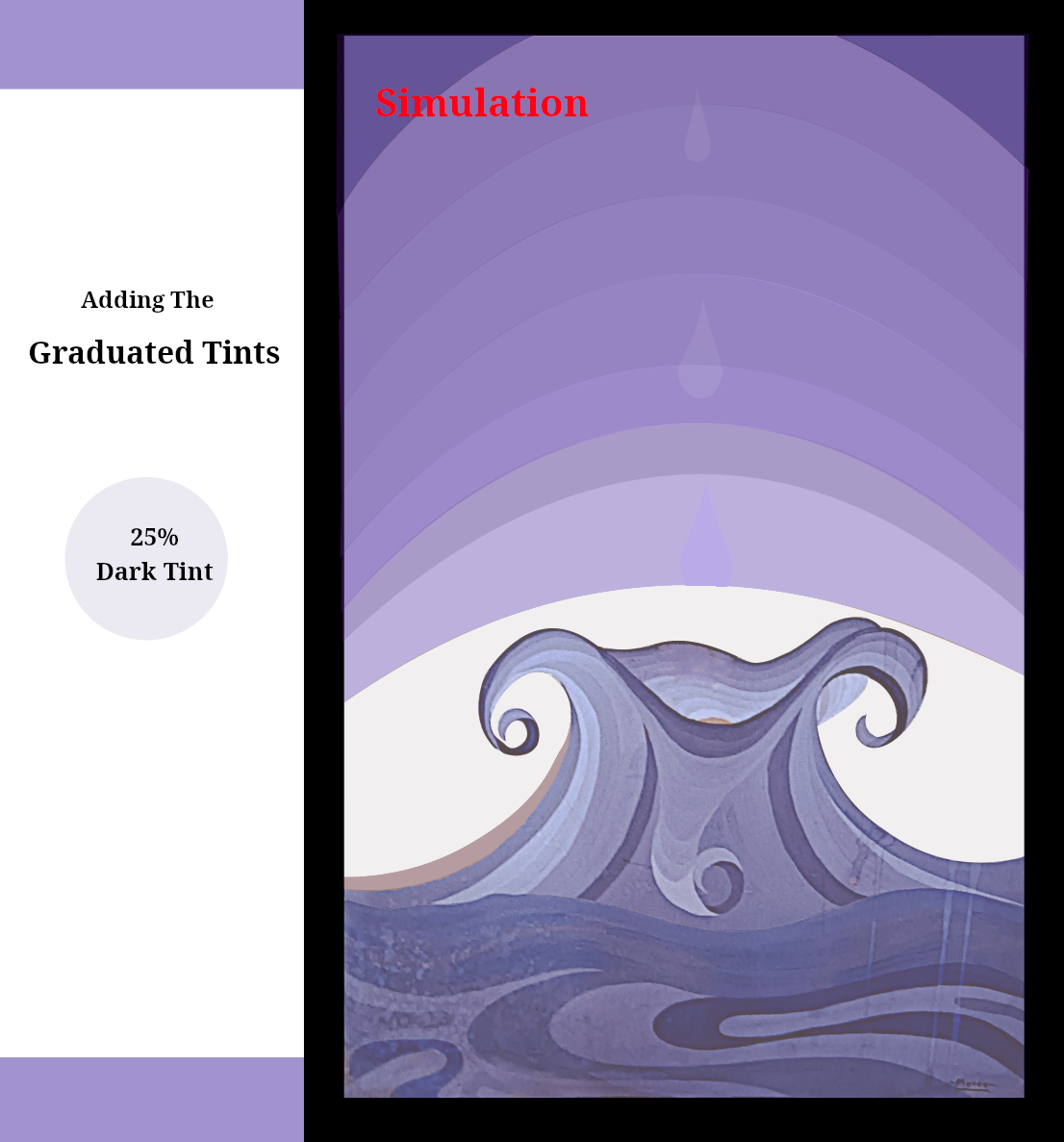

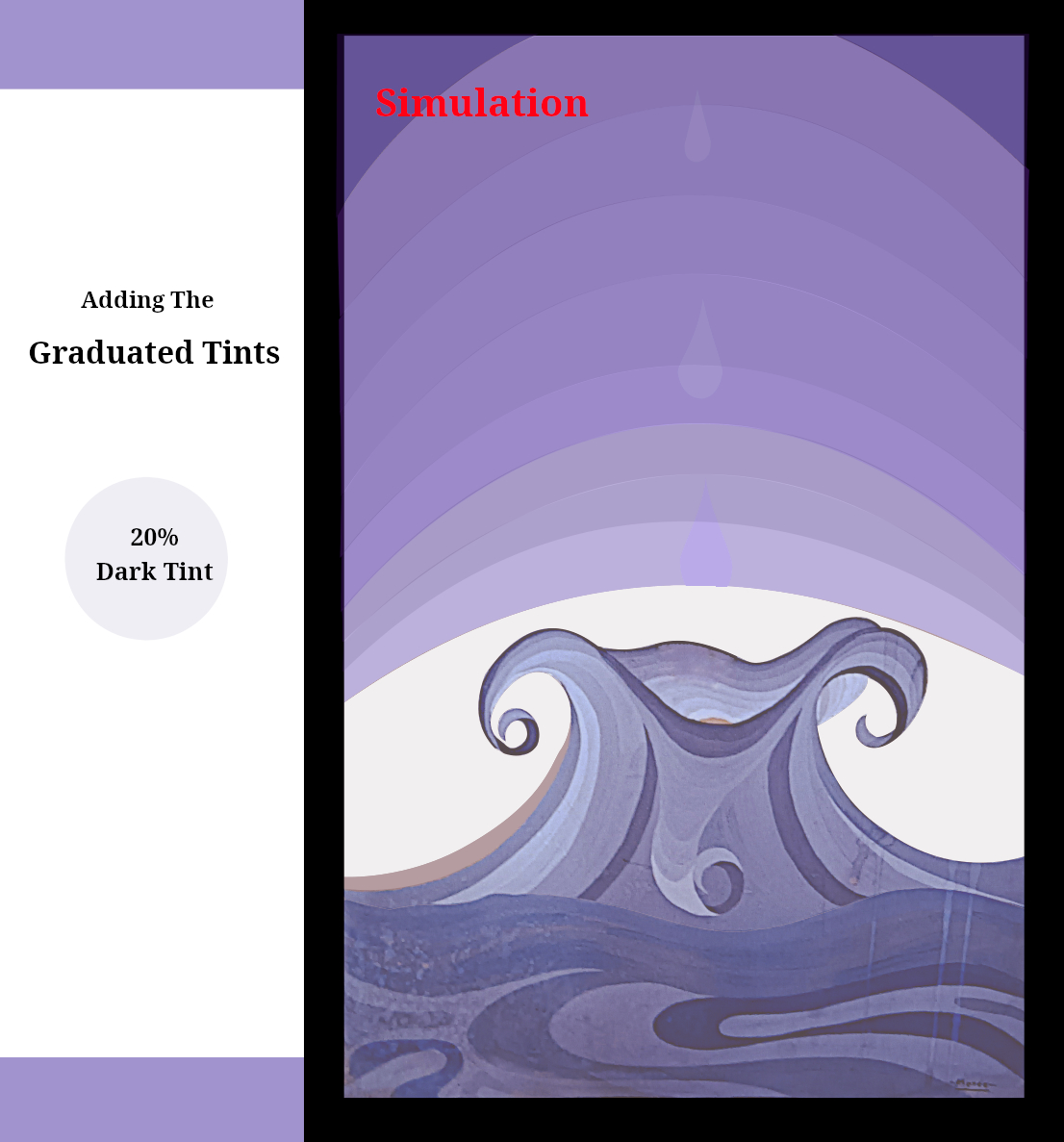

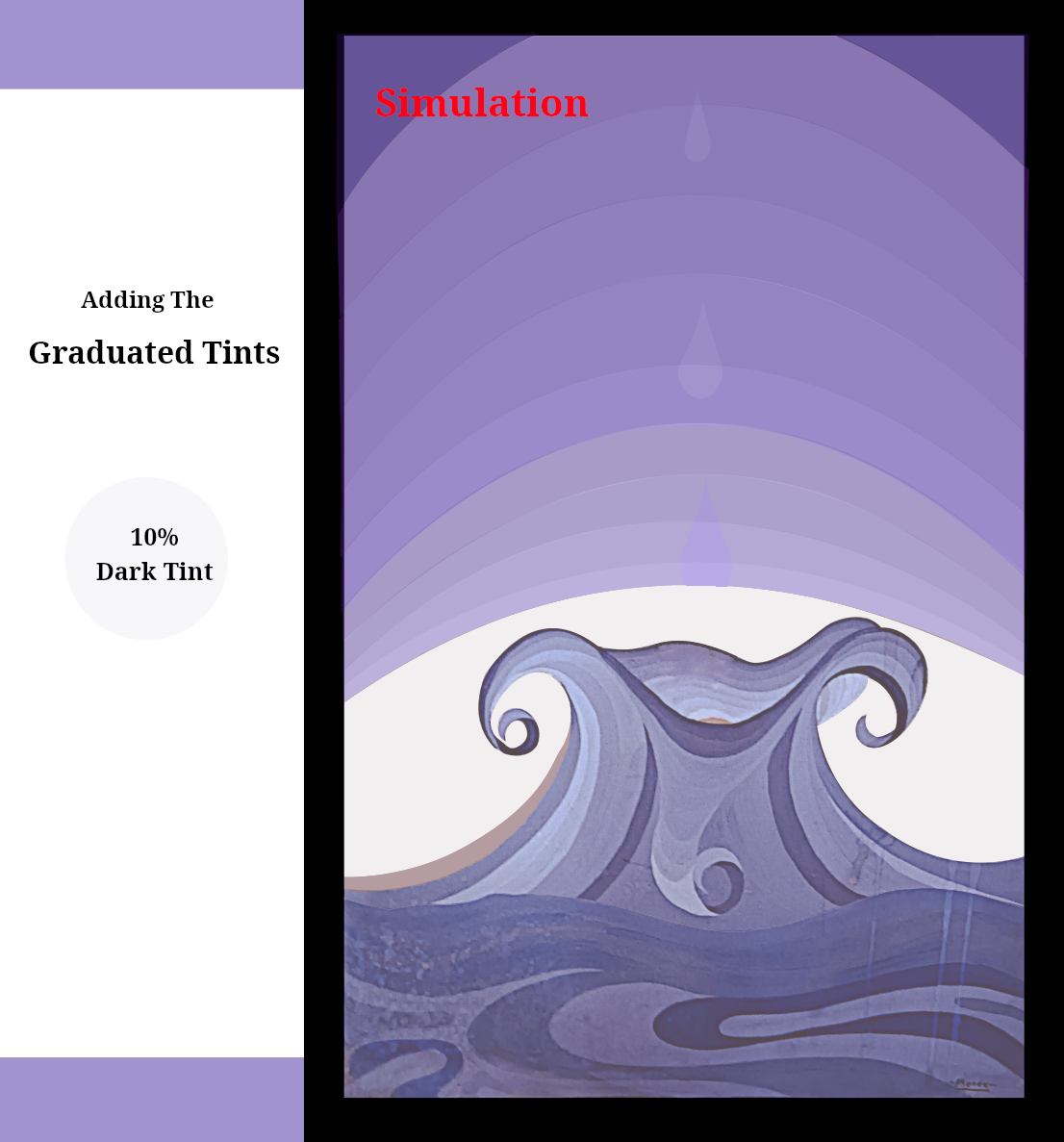

It’s the layers.

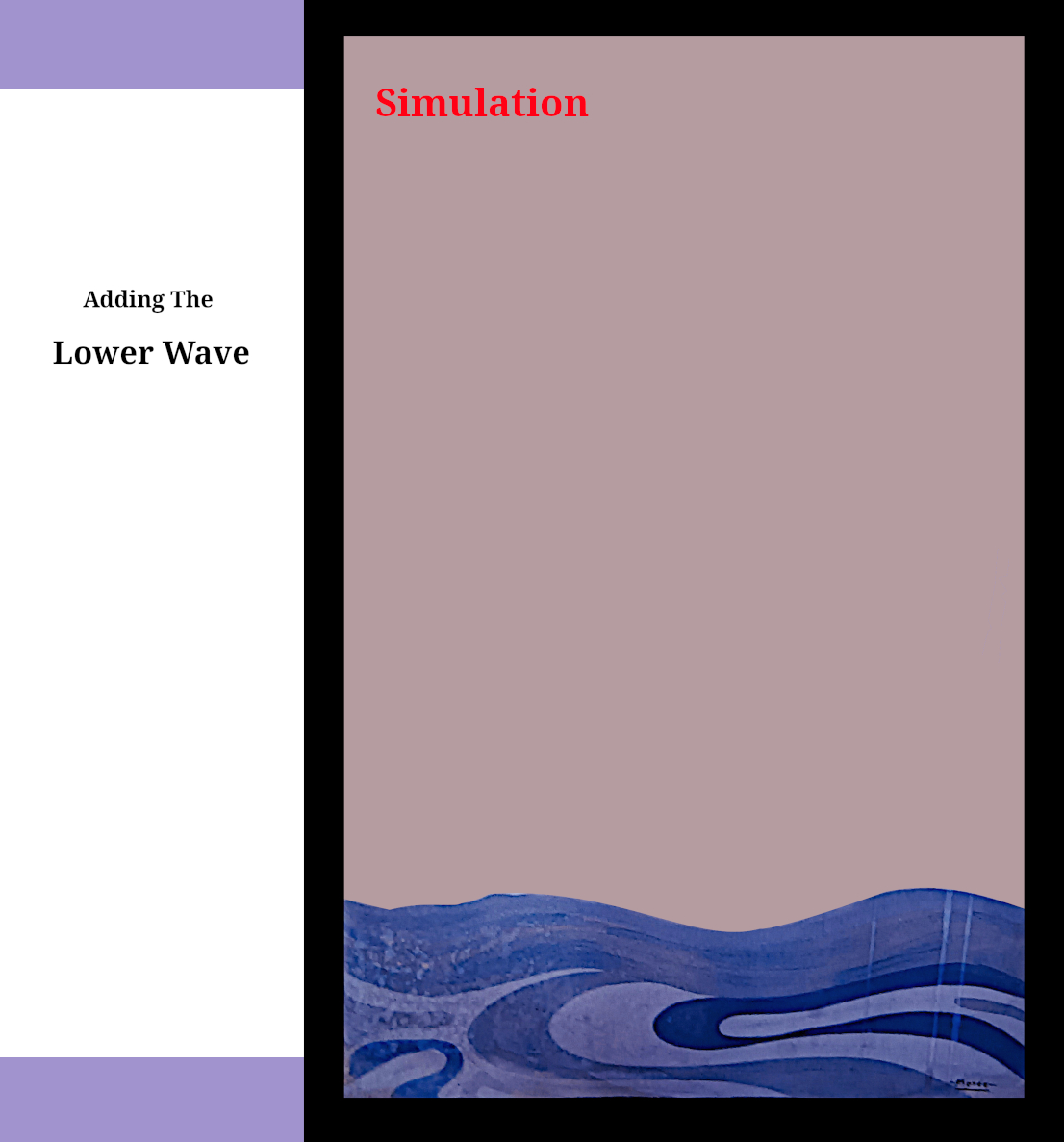

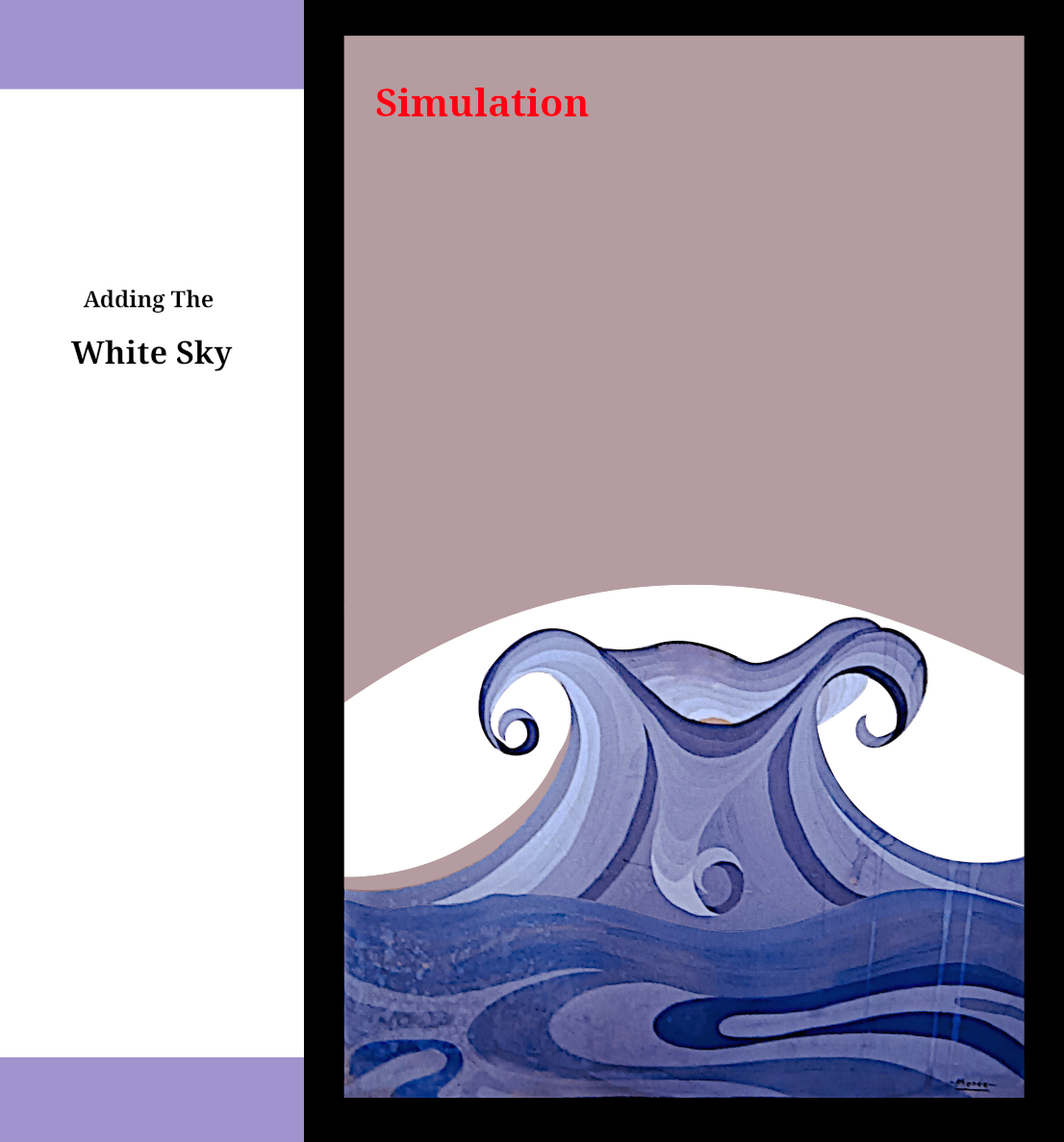

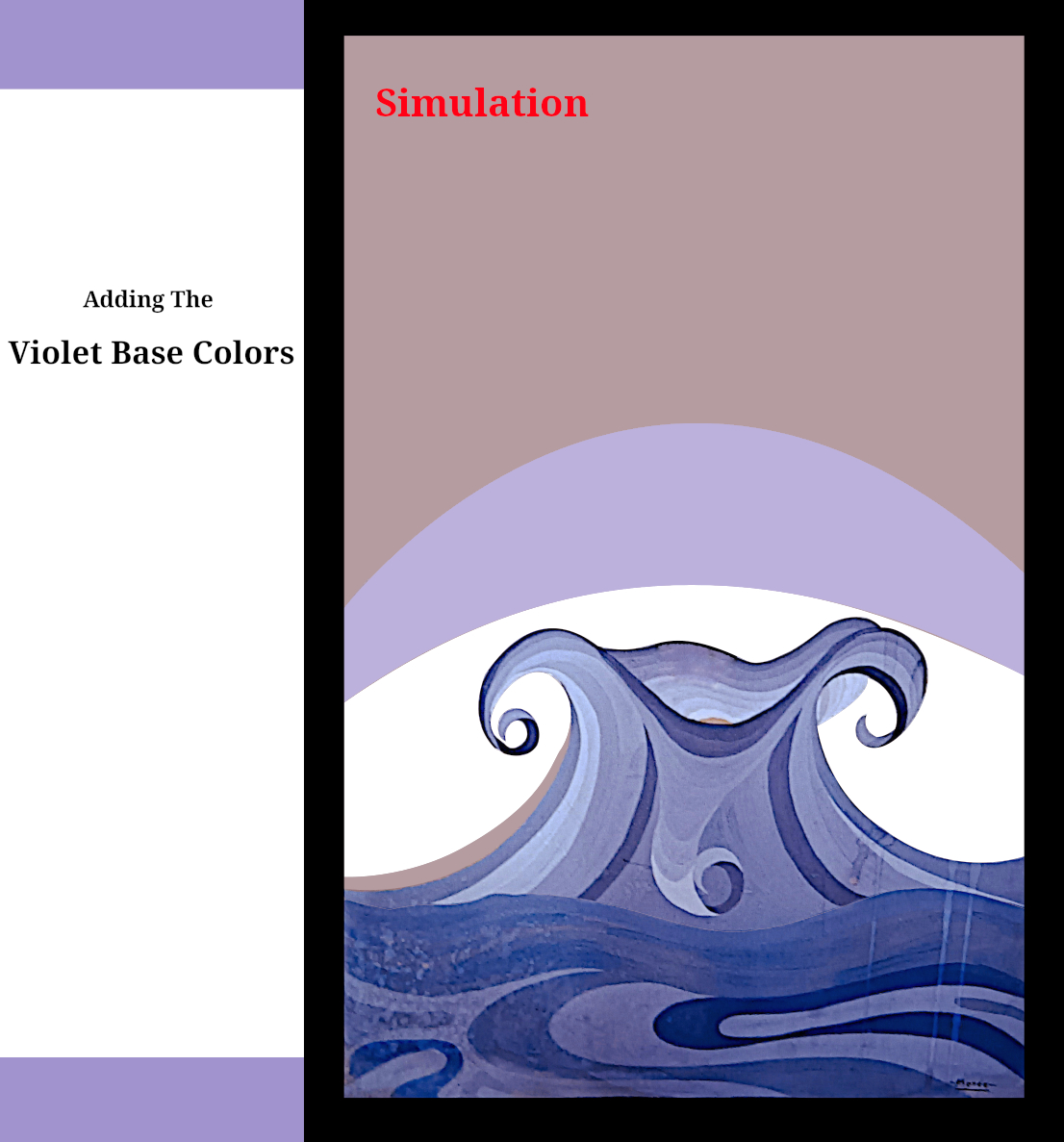

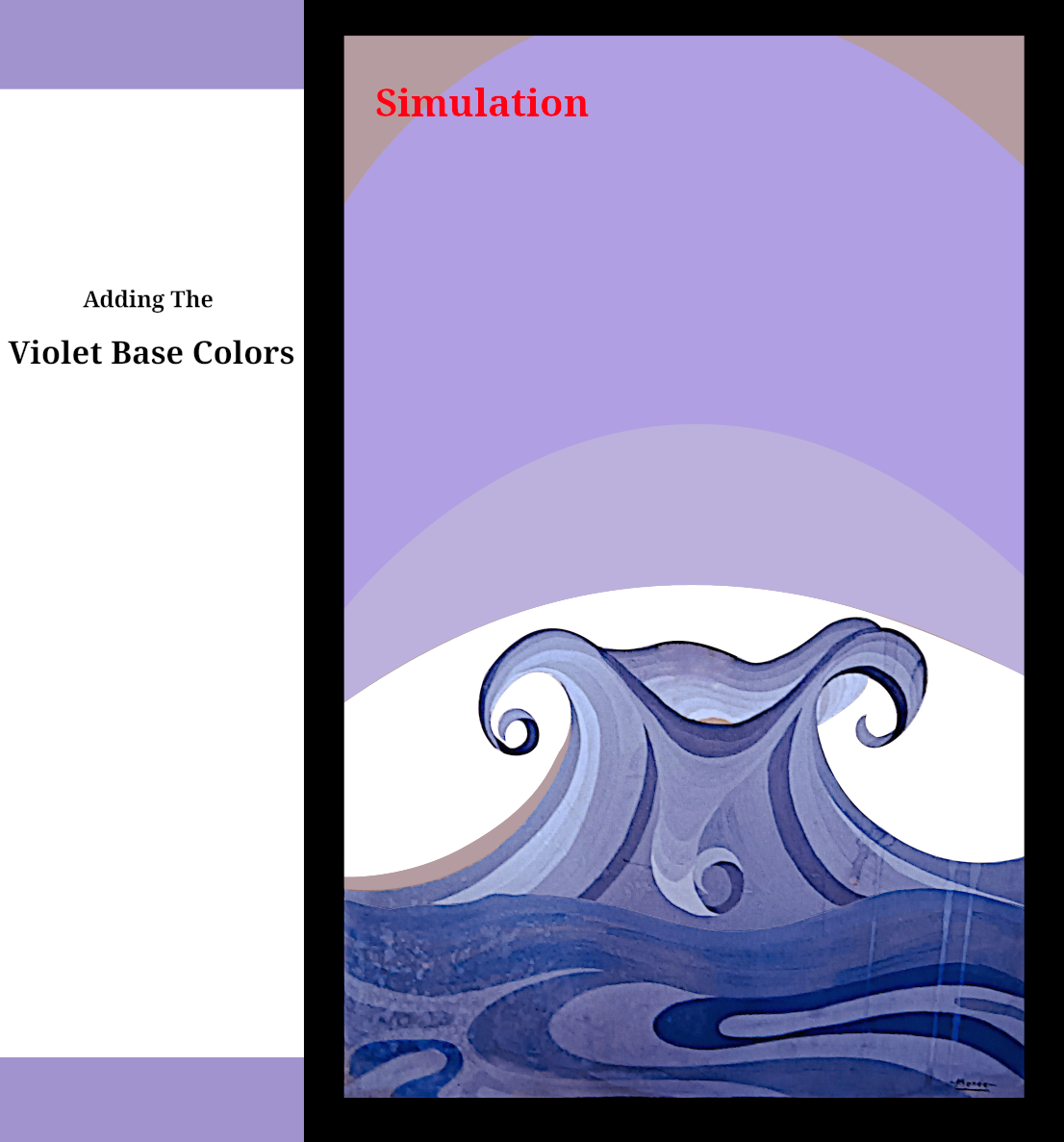

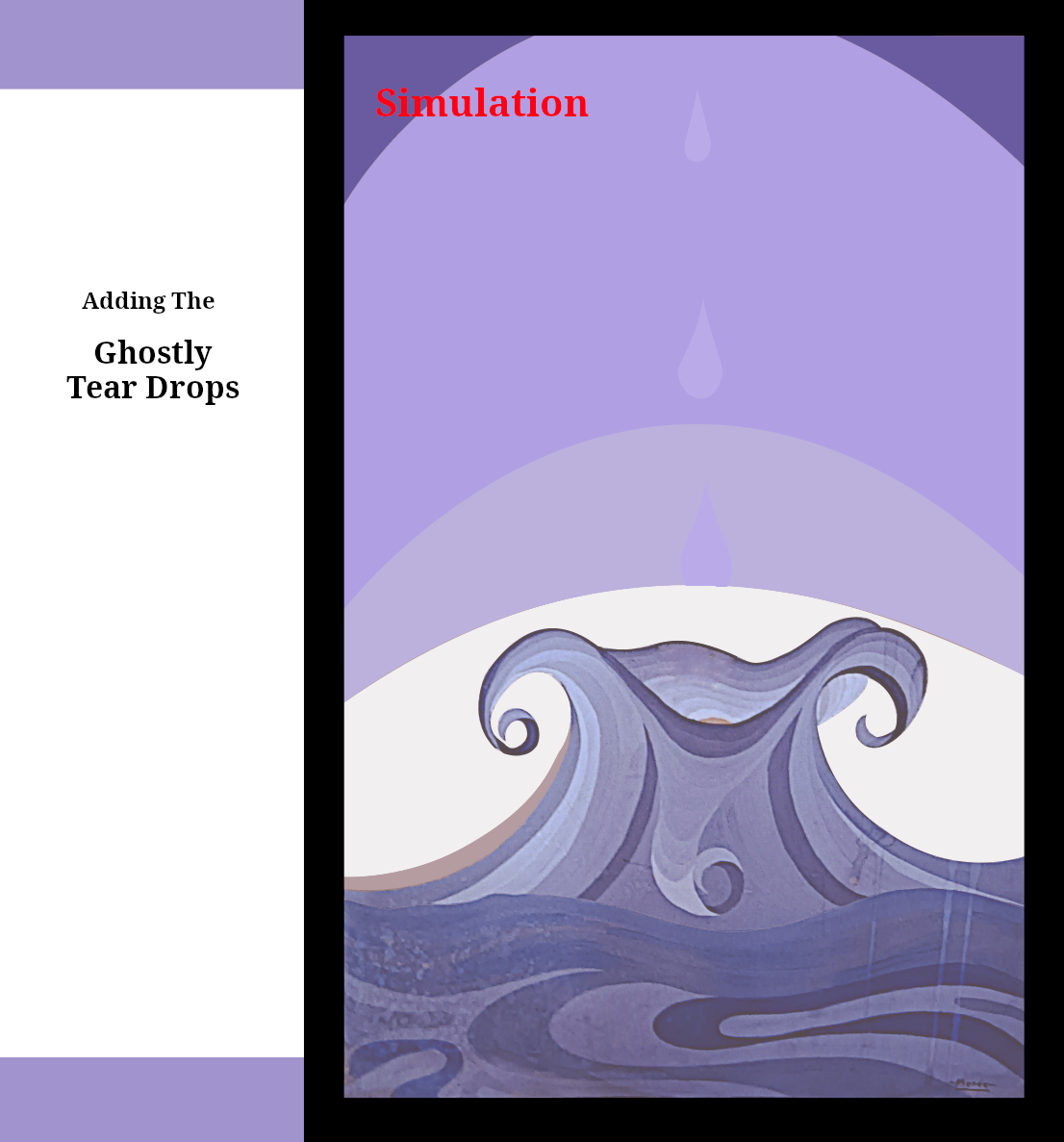

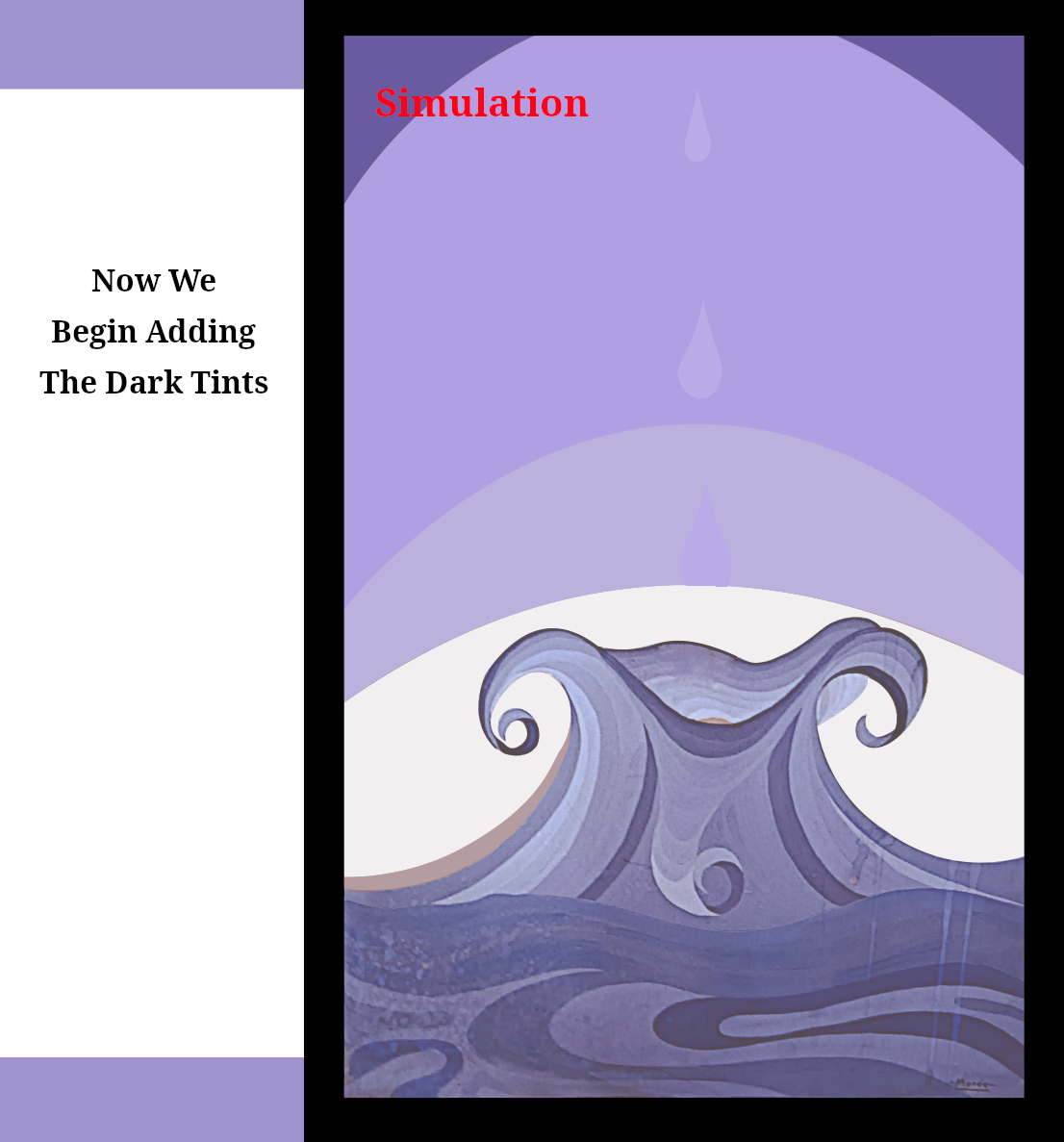

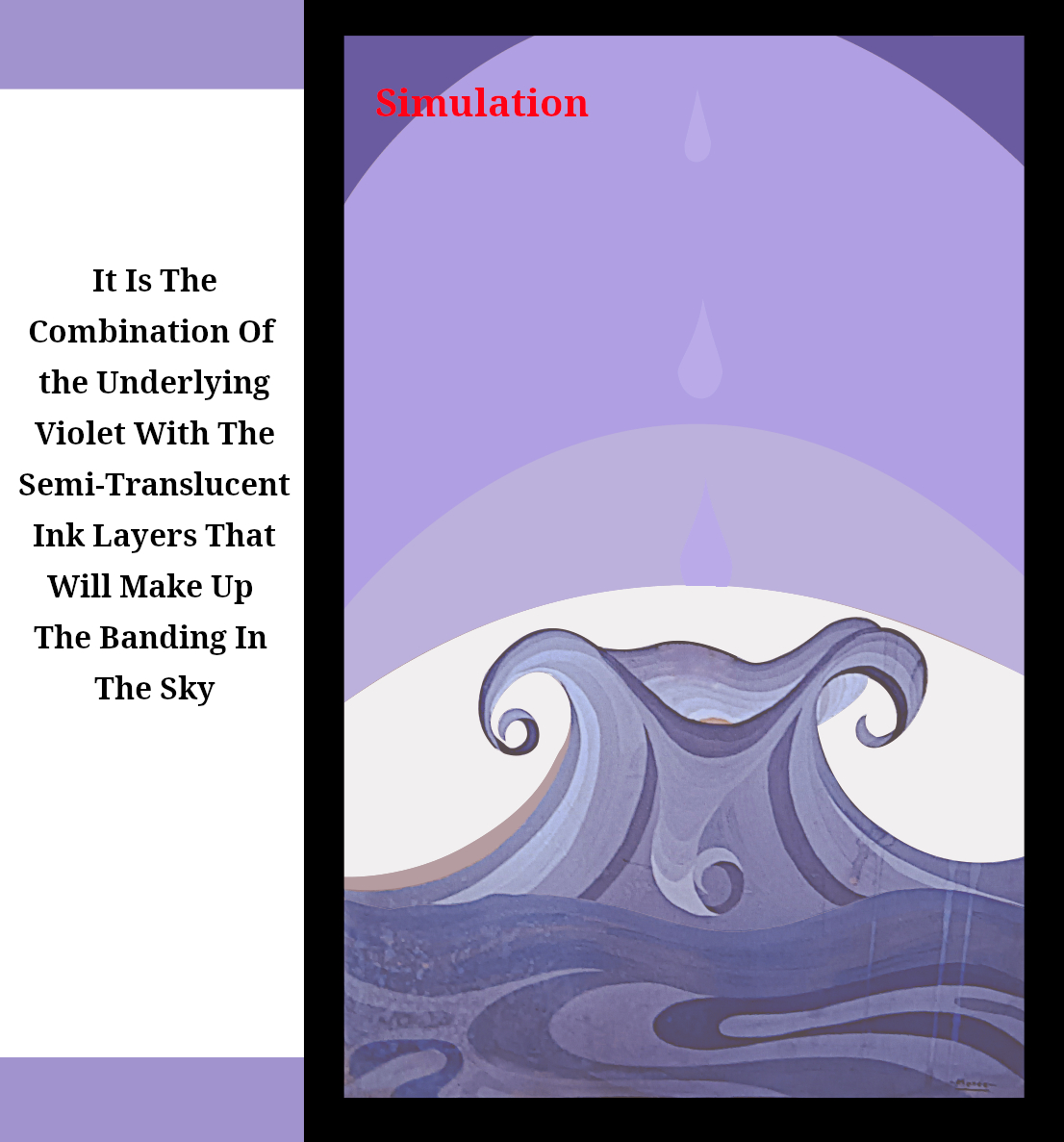

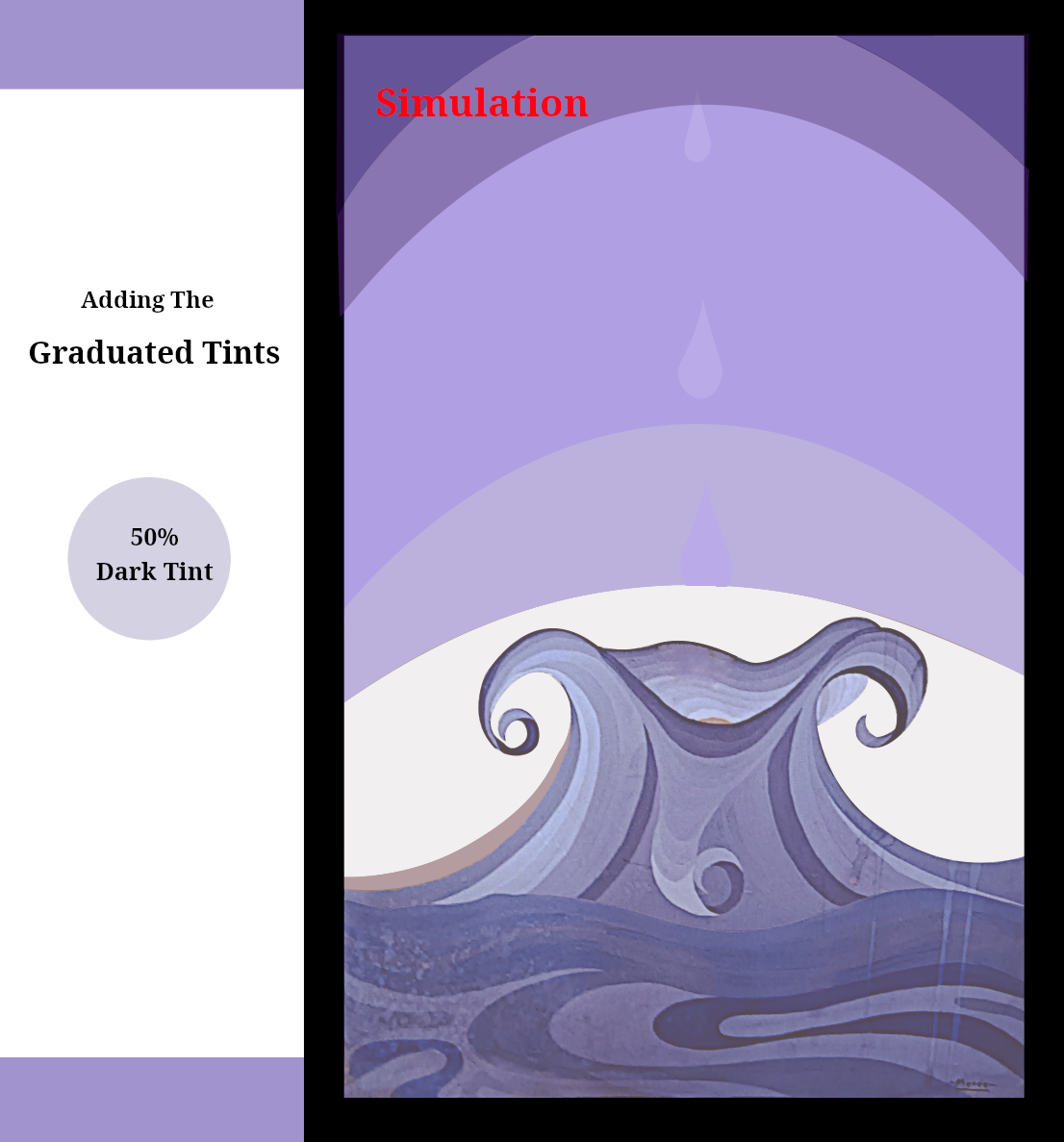

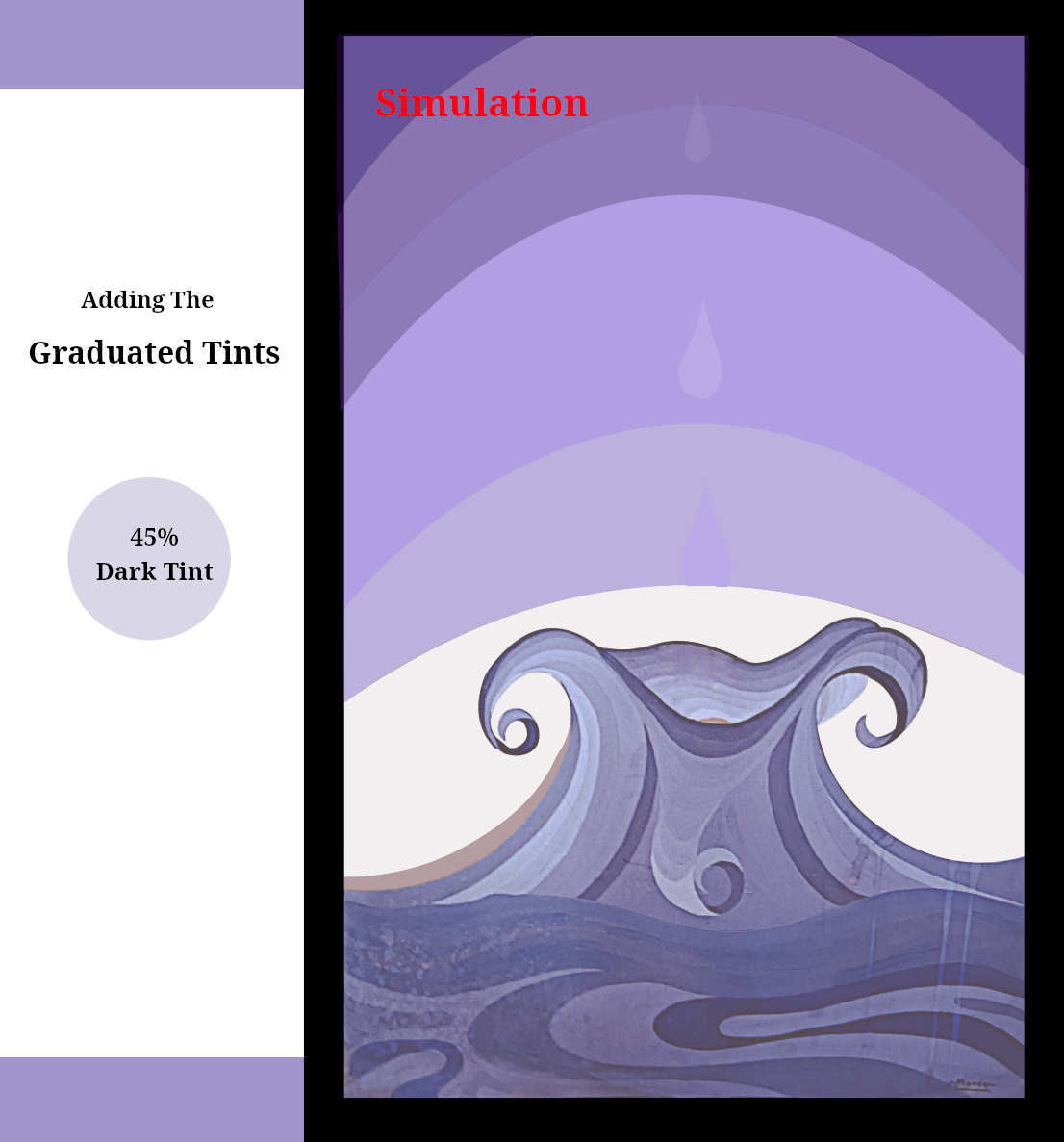

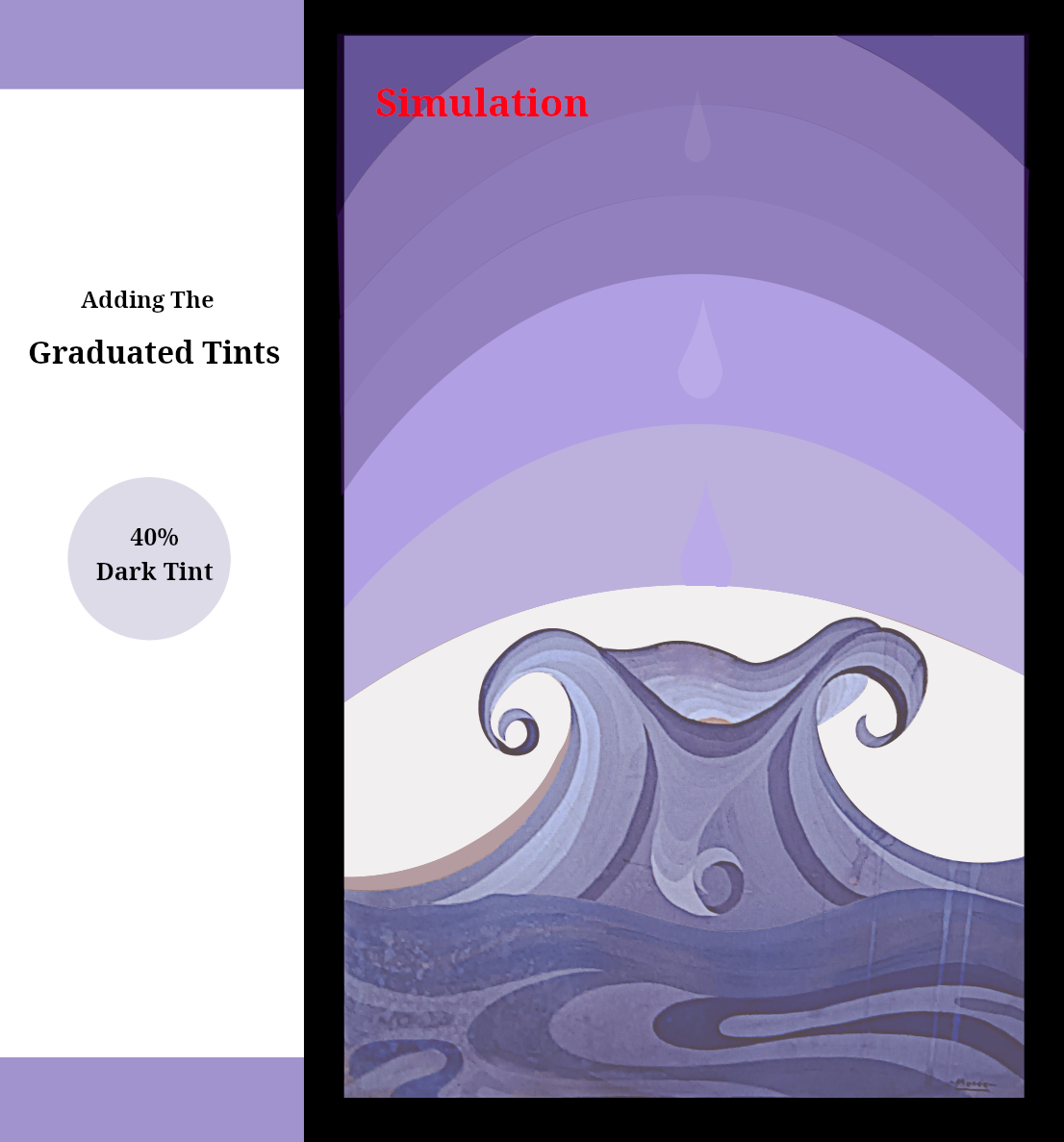

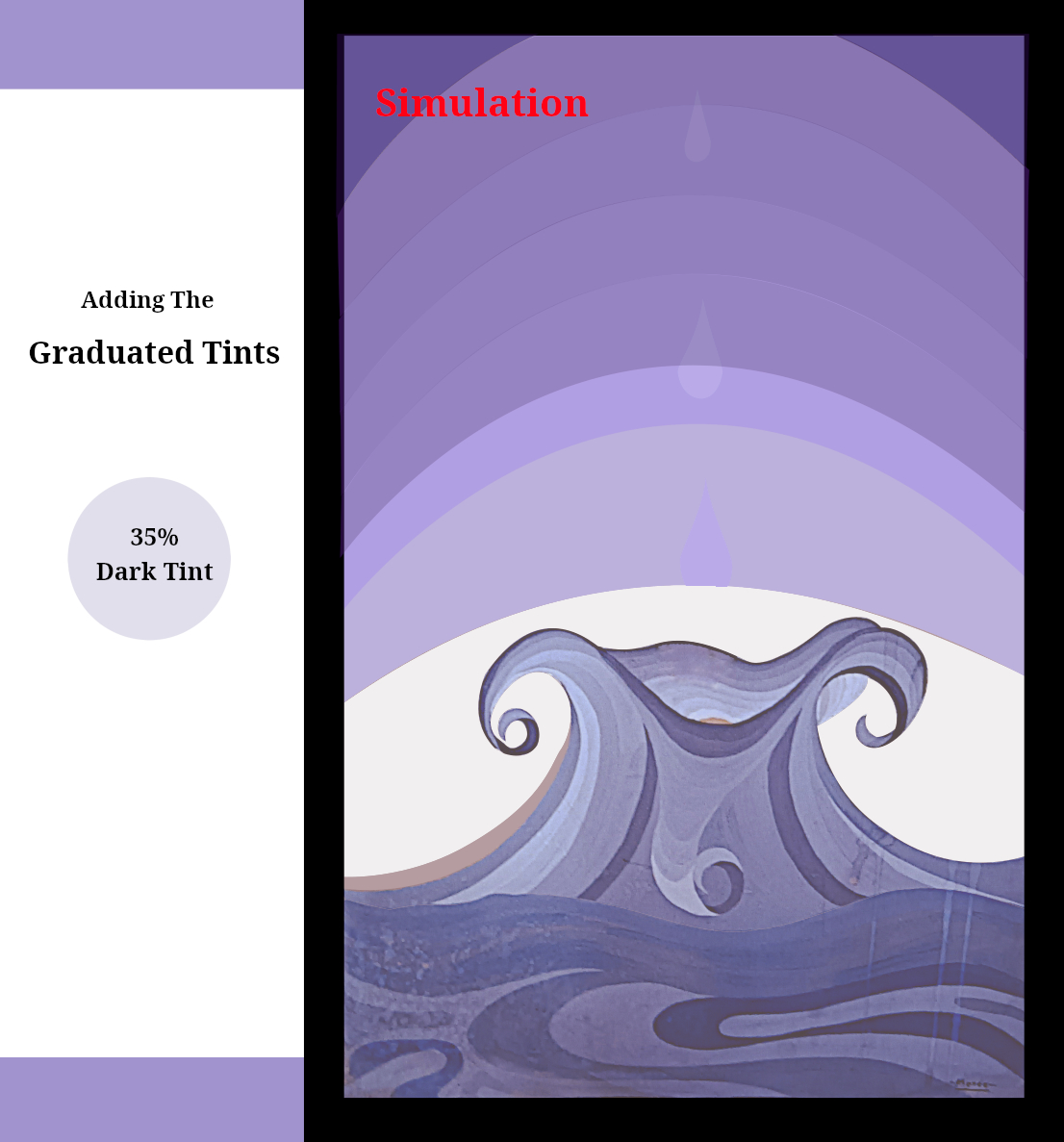

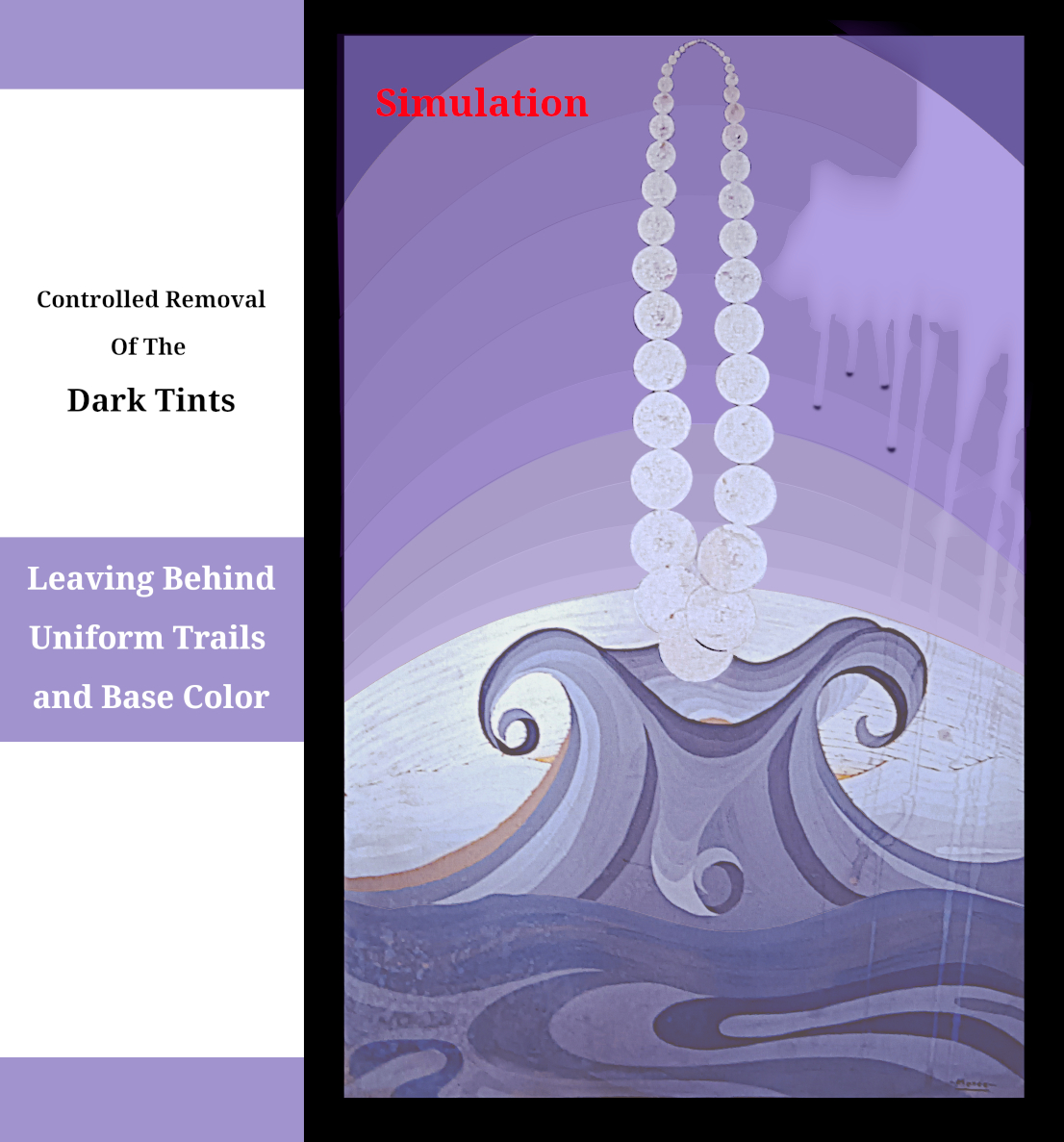

Morée wasn’t painted in a single pass. It was built up—deliberately, strategically—with translucent glazes and thin veils of color. Some of these layers serve no visible purpose in the final image. They’re not decorative. They’re not structural. They’re transitional.

They exist only to be removed.

The entire upper third of the painting shows signs of localized wetting, splashing, dripping, and removal. Alcohol-soluble pigment was laid down, then stripped away—sometimes partially, sometimes completely—leaving behind shadows, ghosts, and streaks of lost image.

This wasn’t a painting that was accidentally damaged.

It was a painting that was constructed to be dismantled.

And once you see that, the stain doesn’t look like sabotage from the outside. It looks like sabotage from within.