An Analysis of Morée

The Artist Leaves His Mark

A Punctuated Timeline

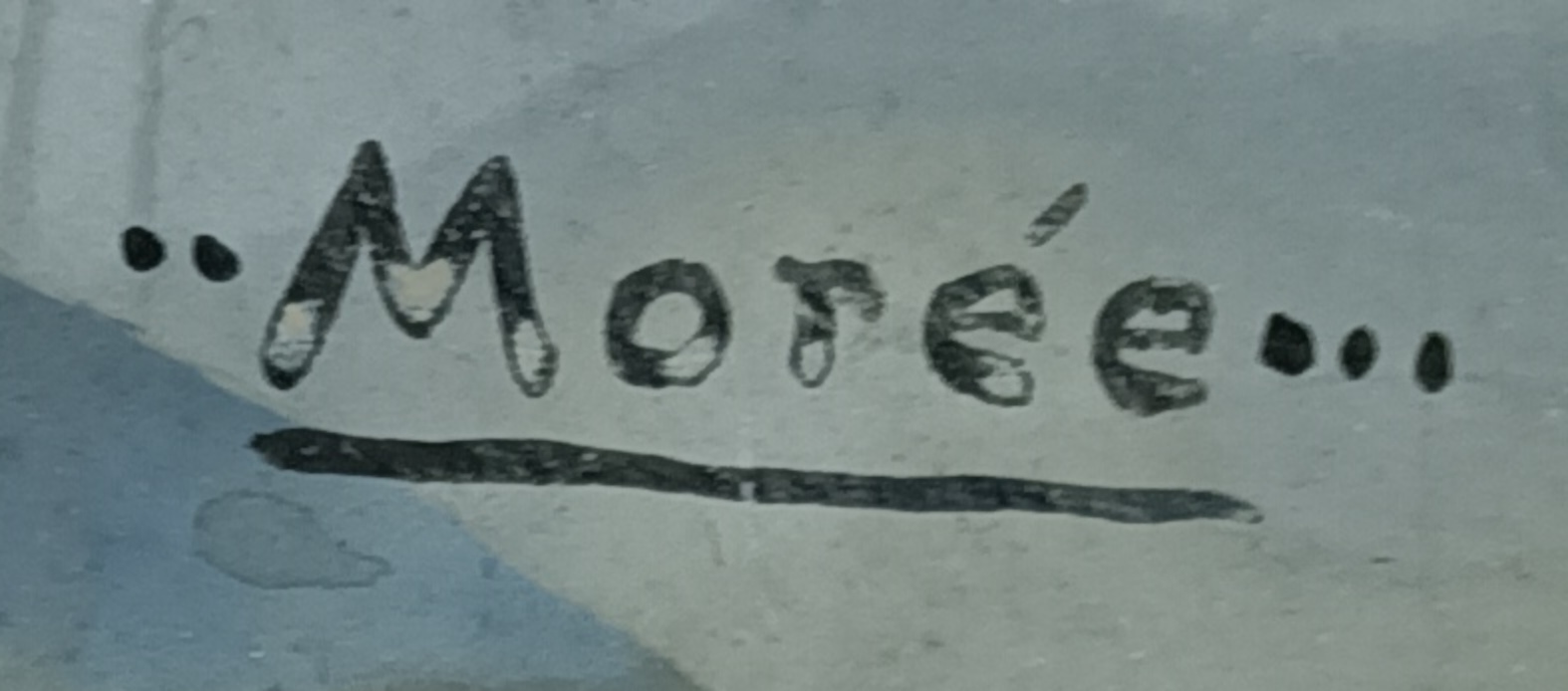

The inscription on Morée—“..Morée…” with two dots before and three after—was likely more than mere typographic decoration. Read in the context of New York’s anti-art gestures of this period, it invites closer scrutiny, and within the Arensberg circle two paintings in particular emerge as natural points of comparison: Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 and No. 3.

The dots themselves are materially and stylistically distinct from the rest of the signature—darker in tone, applied with a separate motion. This is not casual punctuation but a discrete gesture, set apart from the name, and it suggests symbolic intent. In this way, the signature quietly asserts Morée as a bridge—not a sequel, but a correction. It doesn’t advance the series; it rewires its meaning.

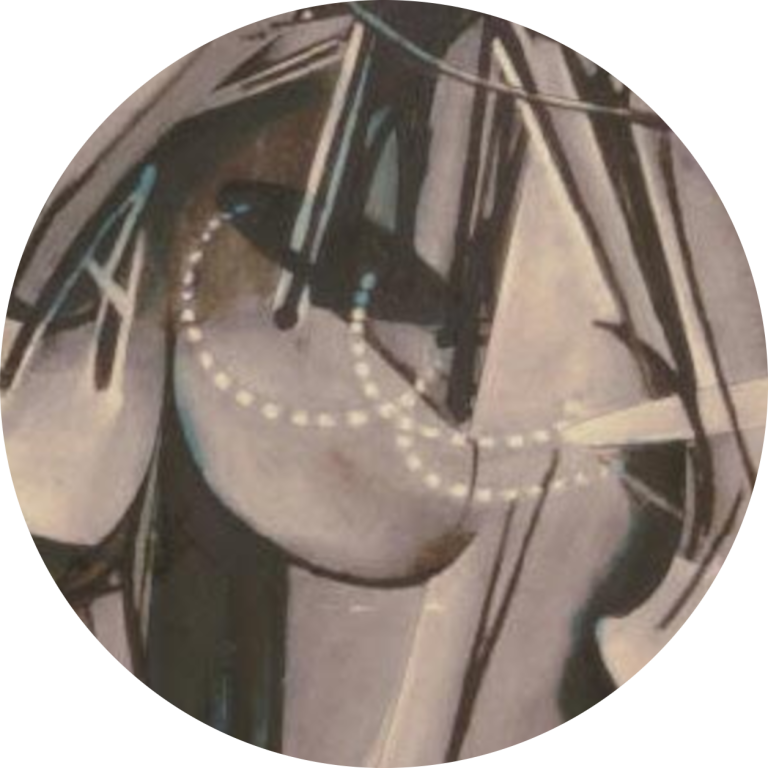

That correction comes into focus when Morée is read as a lens for understanding the Nudes. The elliptical arcs long interpreted as “motion rings” were likely intended as pearls—tokens of ornament meant to feminize the subject rather than mark its movement. In Morée, pearls appear openly, suspended and corroded, stripped of glamour. That image refracts back onto the Nudes, showing the arcs were not mechanical traces but feminizing details. Seen through Morée, the sequence comes into sharper focus, its misunderstood element suddenly clarified.

Duchamp's Disappointment

The Misreading of Nude No. 2

This page explores the complex web of misunderstandings, missed cues, and collaborative tensions surrounding Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), particularly its gendered misinterpretation and the profound consequences this had on Duchamp’s trajectory, the emergence of pre-Dada, and ultimately the creation of the enigmatic painting Morée.

In light of Morée, the uproar over Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 at the 1913 Armory Show was more than a scandal — it may have been the spark that set Duchamp on a path to dismantle painting from within. The derision and misunderstanding the Nude provoked became a challenge:

to push the medium past the point of repair.Morée is the answer to that challenge. It doesn’t just depict — it performs — the death of painting — its surface defaced and its glamour stripped away. In doing so, it turns personal provocation into a blueprint for

Dada’s anti-art ethos.

The Gender Blindness of 1913

Despite the title, American critics and viewers at the 1913 Armory Show almost universally failed to perceive the figure in Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 as feminine. President Theodore Roosevelt famously mocked it as a “naked man going downstairs.” Satirical poems in newspapers imagined the painting as a joke, offering cash prizes to anyone who could locate the supposed nude. One article explicitly referred to it as a male figure — misreadings that likely cut deep.

Decades later, Duchamp recalled the reception with a touch of irony: “One just doesn’t do a nude woman coming down the stairs. That’s ridiculous… A nude should be respected.” He was paraphrasing the reaction of 1913 America, but in doing so, made his own intent unmistakable — to him it had always been a nude woman. It was the viewers who missed the feminine signals, and that blindness became a catalyst for his next moves: pushing painting toward erasure, and ultimately toward the anti-art gestures embodied in Morée.

The Nude No One Saw—and the Seeds of Dada

Among the most suggestive elements in Nude No. 2 are the elliptical arcs, often read as echoes of motion. But what if they were always meant to evoke something more sensual, more human, more bourgeois? Pearls.

Viewed through the lens of Morée, the pearl-like forms read clearly as stylized ornament—dangling in sequence, delicate and deliberate. They offer a feminine counterweight to the otherwise mechanical, Cubo-Futurist fragmentation.

Yet in 1913, no critic described them this way. No one saw jewelry.

No one saw a woman. Duchamp’s gamble—embedding femininity inside

formal abstraction—was misunderstood. If those arcs were meant as pearls, they failed to register. If the figure was meant as female, she was erased.This default to masculinity may have cut deeper than Duchamp ever let on.

The painting wasn’t merely misunderstood—it was misgendered.

What vanished was not just a motif, but a signal of softness, of femininity.He let the misunderstanding stand—then moved on.

But from this misreading came Morée—a private reckoning, and the birth of several coded gestures that would later define Dada.

Morée: A Private Response

Morée must be read within an atmosphere of disappointment and revolt.

If Nude No. 2 was intended as feminine but misread, then Nude No. 3

(a commission by Arensbergs) simply restaged that misunderstandingExecuted in 1915-16 (sometime before Nude No. 3), Morée offers a vision

of pearls corrupted—dripping, degraded, and suspended in erosion.Its signature is scraped with a sharp tool. Two and then three dots are

added beside the name, almost certainly referencing the numbered sequence

of the Nudes.The dots may be a late addition, meant to quietly position Morée between the Nudes — not as a missing link, but as a clarifier.

In that light, it reads as a coded footnote to the uproar of 1913, restoring the feminine reading that No. 2 had lost in translation. Less a continuation than a correction, it reframes the sequence by making the gender explicit.

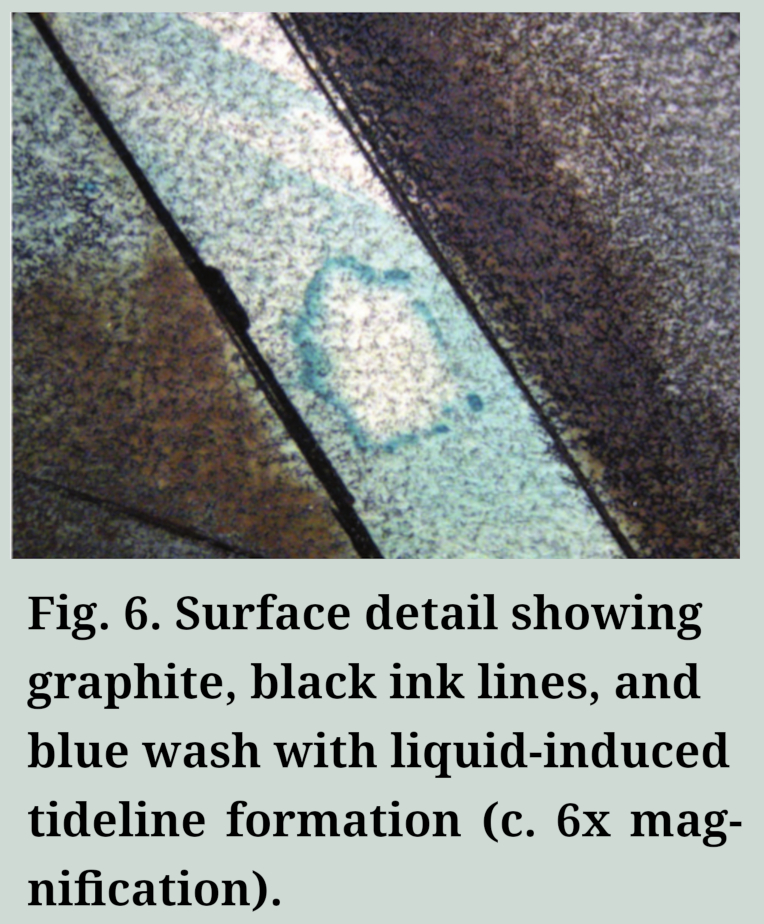

One more possible link: Conservators believe a drop of alcohol or solvent hit the blue ink wash in No. 3, causing the pigment to repel and create a distinct halo.

This could be just an accident, or it could be intentionally created. It is known that Duchamp used